First off, I congratulate the computer Watson for its successes on the show Jeopardy!. Watson seems to be holding Ken Jennings and the other guy who isn’t Ken Jennings at bay, just as Watson’s older brother Deep Blue took two wins against chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997. Truly, the era of technology has advanced far beyond what we thought was science fiction.

But what if I told you that this run of “artificial intelligence” – in which a human is fooled into thinking that a machine actually can think and perform like a real person – had been demonstrated by Thomas Edison as far back as 90 years ago – and one of the largest demonstrations Edison ever conducted was in Albany, at the Washington Avenue Armory?

I see that I have your attention.

Let us travel back in time, to the invention of the phonograph. From the 1890’s until 1929, Thomas Edison’s company manufactured cylinder recordings, while two other music companies, Columbia and Victor, produced flat disc records. Flat disc records were more durable and easier to store than cylinder records, and the Columbia-Victor manufacturing duopoly garnered the larger share of the market, leaving Edison in the dust.

Undaunted, the Wizard of Menlo Park invented a new type of phonograph, a “Diamond Disc” phonograph. It played flat records, just like the Victor and Columbia phonographs, but an Edison Diamond Disc player had several specific incompatibilities with its phonographic brethren. The records were almost a quarter of an inch THICK – they were so durable, Captain America could have used one as a replacement shield. The records rotated at 80 revolutions per minute, as opposed to the standard 78 RPM of the day. And in another case of incompatibility, the grooves in Edison’s Diamond Disc records were “vertical cut,” in that the needle picks up the sound information on the bottom of the record’s grooves, as opposed to the “lateral cut” of other records. In fact, the diamond-tipped stylus of an Edison Diamond Disc phonograph could last for decades, while the steel needles in your average Victrola had to be replaced after EVERY PLAY.

Dozens of Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph stores popped up around the United States, including one that operated from 1917 to 1927 on 74 North Pearl Street in downtown Albany. In fact, most of the Diamond Disc phonographs still have engraved nameplates inside their lids – nameplates of the stores from where they first originated.

Now back to Edison. To promote his revolutionary phonograph, Edison took his product through several promotional “tone tests.” People were invited to a concert hall. Edison would have one of his vocalists perform a song, and halfway through the song the vocalist would stop singing – but the phonograph next to that singer would continue playing the record, with that artist’s vocals on it. Many attendees of tone tests claimed (at least according to Edison’s advertising campaigns) that they could not tell the difference between a live vocalist and a phonograph record – thus passing what would later become the Turing Test. Edison used these claims to promote the superior sound quality of his Diamond Discs over his competition’s products.

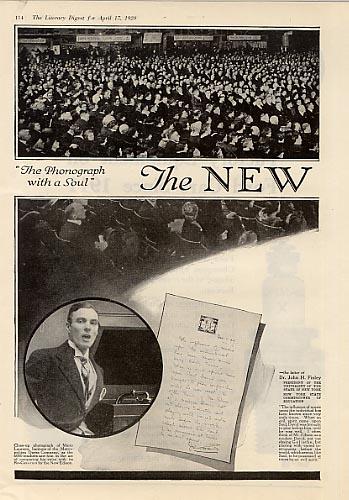

One of Edison’s most successful tone tests occurred on November 25, 1919. At the time, the New York State Teachers Association was in the midst of their annual convention, and 10,000 teachers and principals came to Albany for the three-day event. During the convention, 6,000 members of the NYSTA crammed into the Washington Avenue Armory to hear Metropolitan Opera baritone Mario Laurenti perform alongside a Diamond Disc phonograph. Again, it was reported at the time that the audience could not tell the difference between the flesh-and-blood baritone and the mahogany-and-brass machine.

One of Edison’s most successful tone tests occurred on November 25, 1919. At the time, the New York State Teachers Association was in the midst of their annual convention, and 10,000 teachers and principals came to Albany for the three-day event. During the convention, 6,000 members of the NYSTA crammed into the Washington Avenue Armory to hear Metropolitan Opera baritone Mario Laurenti perform alongside a Diamond Disc phonograph. Again, it was reported at the time that the audience could not tell the difference between the flesh-and-blood baritone and the mahogany-and-brass machine.

Edison used the tone test, along with a letter of praise and endorsement from Dr. John Finley, President of the State University of New York, in advertisements for years, along with calling his music player a “phonograph with a soul.” Yeah, it’s probably a stretch to equate a record player to Pinocchio, or even Motoko Kusanagi, but at the time Edison’s Diamond Disc player was truly a viable listening alternative.

But if the records were superior in quality to whatever Victor and Columbia were producing, what happened?

Well, a few things happened. Edison had to approve every recording, and his love of Victorian parlour ballads and “old home” songs didn’t match with the rise of early jazz and orchestral music. And when you’re asking a man who was almost stone deaf to act as your record company’s A&R man, well…

Also, as more record companies came into existence, they chose to use the Columbia-Victor phonograph format, leaving Edison behind.

And as the sales for Edison Diamond Discs began to wane, the dealerships closed up. The shop at 74 North Pearl Street? It became a shoe store in 1927. And by 1929, Edison stopped production of the Diamond Disc phonograph. Perhaps it was the Betamax of its time – or maybe even the HD DVD of the Roaring 20’s, a superior format that lost out to its competition.

But on that night in November 1919, Edison’s Diamond Disc player was able to fool an audience of 6,000 teachers, principals and administrators into believing that it produced not a recording, but the actual living voice of a famous opera singer.

And maybe 90 years from now, someone will too look back at our time and marvel at how quaint it was that a computer competed on a quiz show.

We’ll check back on this in the year 2101.

NOTE: Edison Diamond Disc graphics above came from the eBay auction at this link.

One thing that gave me hope that the machines may not be ready to take over….when it came to double jeapordy,Watson didn’t have the “thinking” needed to risk enough to take the lead, but not screw himself if he missed the question.

LikeLike

Or maybe Watson just knew He was right when he wagered on that Final Jeopardy answer. Since the Day before he was wrong and wagered much less.

LikeLike

This is an interesting story Chuck, but it has nothing to do with Watson’s AI and this “tone test” is nothing like the Turing test.

I think this post would have been fine without the attempt to draw traffic by connecting it to a popular current event.

LikeLike

Actually, it is the same thing. Edison demonstrated that a machine – in this case, a phonograph – could reproduce a sound quality that equated a live human voice. And that people could be fooled into thinking that the live vocalist was still performing, when in fact, he wasn’t. Thus fooling a person into thinking that a machine had human qualities. I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree on that one.

LikeLike

No, sorry Chuck, we will disagree to disagree 😉

You said:

“But what if I told you that this run of “artificial intelligence” – in which a human is fooled into thinking that a machine actually can think and perform like a real person – had been demonstrated by Thomas Edison as far back as 90 years ago”

Edison’s “tests” had nothing to do with thinking. No there’s absolutely no connection to Watson on Jeopardy, because it is not replicating a human perfomance by rote. The tone tests were in no way a test of AI, but a test of recording quality; are you really suggesting that the audiences believed the recording was thinking? When we take that part out of your statement, the comparison to Watson completely falls apart.

And as for this:

“Many attendees of tone tests claimed (at least according to Edison’s advertising campaigns) that they could not tell the difference between a live vocalist and a phonograph record – thus passing what would later become the Turing Test.”

No, this is nothing like the Turing Test at all. The key component of the Turing Test is that the human subject is interacting with the AI. As I’m sure you know, the concept is that if a person of average intelligence is having a back-and-forth text-only conversation and cannot determine if their conversation partner is not human (I believe Turing limited the time to 5 minutes and certainty to something like 75%), the AI has passed the Turing Test. Even if we were to expand the test to audio, the audiences never interacted with these recordings. It was a recording, played back, that’s all. It’s like saying that a computer fed and then spitting out the entirety of Moby Dick has passed the Turing test.

Chuck, this is interesting and I like the local tie. But come on, there is no relevance here to Watson and all that’s left is to assume you added that to the title and intro as a way to grab attention and some search hits.

LikeLike

There’s another reason why Edison’s recording company ultimately failed. He himself selected the artists, and due to his lack of classical music knowledge, allowed the top talent to go to Victor and Columbia. The principal example is Rachmaninoff, who left Edison for Victor in 1920, after recording some of those Diamond Discs.

dd

LikeLike

This is a great piece! I collect 78s and gramophones myself and marvel at the sound they can be produce. There really is nothing like hearing a record played on a machine for which it was originally intended, but I digress.

I agree with you that the Watson phenomenon and the Edison exhibition are more similar than not. To me it isn’t just about the technology employed to ‘fool’ an audience. It’s more about the promotion of a product. What surprised me more than watching Watson lay waste to two venerable past Jeopardy champions was the shameless IBM advertising that went along with it, as in “Aren’t we brilliant for inventing Watson? Now buy IBM!” Edison was shameless in the promotion of his own products and this often lead to the destruction of his own creation. He clung to cylinder technology long after it was obvious that the disc was the dominant and more successful medium (thanks to Victor’s success). Columbia got out of the cylinder business in about 1908 and went to lateral cut discs. When Edison acquiesced to disc technology he still stuck to vertical cut records which was already on the way out (Pathe, the only only major producer of vertical cut records, started producing lateral cut records around 1920) and the Diamond Disc invention was nothing more than Edison’s take on old technology. That said, Edison didn’t do his company any favors by insisting on personally approving every singer’s recording.

I’ve heard Diamond Discs played on Edison machines and while they sound marvelous, the technology is esoteric and was in 1920 even by the standards of the day. After all was said and done, Victor won out not only because they were a smarter company, they produced better machines, better sounding records, and were able to sign the best artists. The only other label that could come close was Columbia (whose acoustic records incidentally play best at about 80rpm, not 78…and Victor acoustics play roughly at around 76rpm…the 78rpm standard is, well, not very standard.)

Still, a great post, Chuck! I think you and I could talk records, eh?

LikeLike

At least at this point he had stopped killing elephants.

LikeLike

Hey B, Rather petty and petulant to chastise Mr. Miller for giving us a nostalgic glimpse of an Albany event from the past. I personally am very grateful for the info and yes, if you insist, it DOES COMPARE WITH THE WATSON PERFORMANCE. Chuck, give us more about our old, dear city!

LikeLike